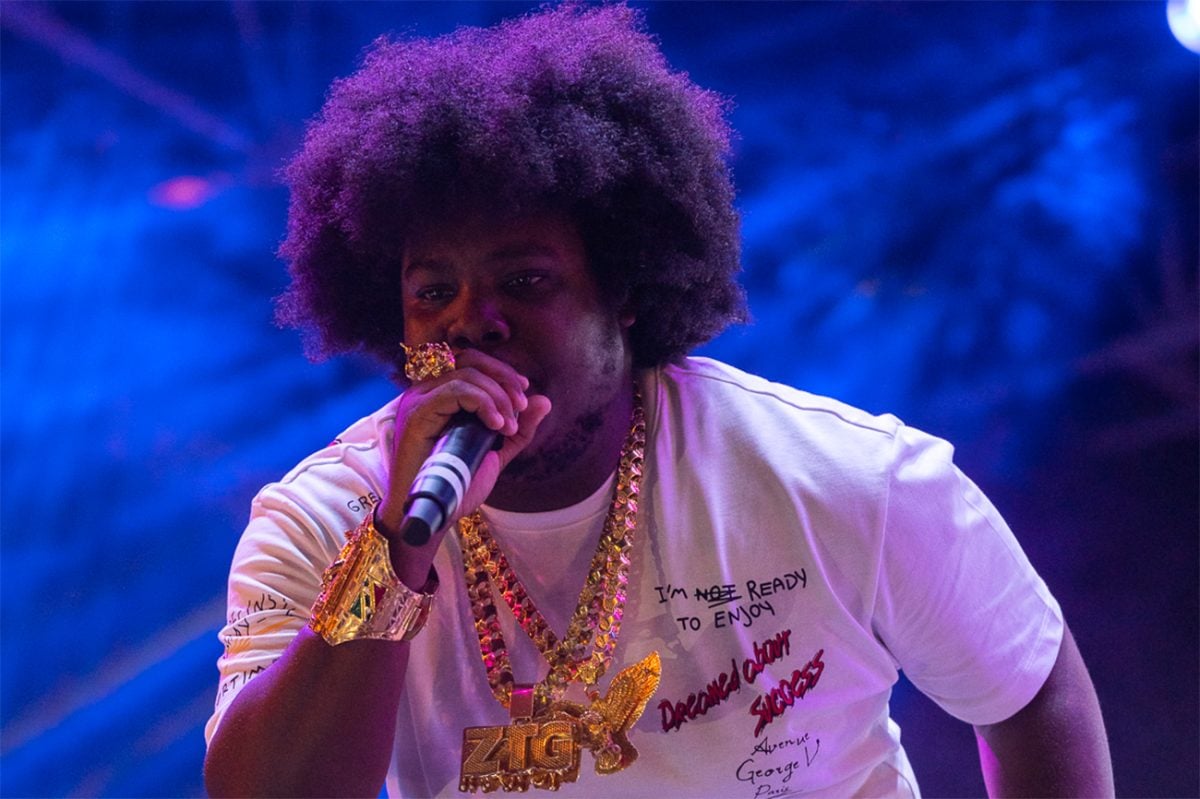

Byron Messia Declares ‘Talibans’ A “Dancehall Masterpiece” Amidst Criticism Of Him Calling It Afrobeats

Amidst the brouhaha surrounding the musical genre of his song Talibans, Jamaican-born Kittician artist Byron Messia has recanted his recent statements in which he alluded to the track being Afrobeats and now says he considers it “Dancehall” because of its “melodies and creativity.”

The 23-year-old flew into Jamaica a few days ago to do the rounds, one of his stops being an interview with Television Jamaica’s veteran entertainment journalist Anthony Miller, to do what the no-nonsense media man described as “damage control.”

After discussing other topics, ranging from Messia’s Kittician citizenship to other comments which had earned him the ire of many Jamaicans, Miller zoned on the controversial issue of the genre of Talibans, the beat for which the journalist noted was “plucked from YouTube,” and which many Jamaicans, who have been aiming at the youngster, have erroneously labeled Dancehall.

“Talibans is a Dancehall song?” Miller asked Messia, who had described the song as a “masterpiece,” during the interview conducted in Ocho Rios.

Messia replied: “I call it a Dancehall song. People been saying it’s an Afro song, but the reason why I will call it a Dancehall song, is because the melodies weh mi use an di creativity behind of it all is very Dancehall-like. An yuh know seh Dancehall run deepa dan just being Dancehall as music.”

“But the truth of do matter is, no matter if you want to call it a Dancehall song, it a guh have di beat for them, weh create genres an charge up genres an distribute genres, dem a guh mek yuh know: ‘no, it is an Afro song’ but me wi consider it as Dancehall song,” the Save Me artist added.

The beat for Talibans, though, is an amalgamation of Afrobeats and Trap. It cannot be considered Dancehall as it is devoid of Dancehall’s drum patterns, the core element that distinguishes the genre from other music forms.

Messia had earned the wrath of some Jamaican music fans over the song, after admitting to Capital Xtra’s Ras Kwame that Talibans, which Spotify placed on its official Dancehall playlist, was an Afrobeats track. At that time, the track held the No. 4 position on the US iTunes Reggae Songs chart.

Messia had said he had initially intended for the song to be a ‘ladies’ track, but he decided to go against the grain and inject some ‘griminess’ into the Afrobeats genre, known for love and little or no bellicose content.

“Is a gyal song I was about to build on it innuh, den mi seh ‘Nah, yuh know seh when yuh listen to Afro[beats], is bare rebellious and love songs yuh only a hear? Yuh nah hear no war or no griminess pon dem beat deh… Yeh, so if you really think ‘bout it – a jus dat yuh a hear – rebellious songs and loving songs. No griminess. Suh mi jus seh, ‘Yuh know wa? Mi ago apply dat and see wa gwaan… and see it deh… Mi jus’ yow, mi ago do somethin’ different, mi ago switch it up and mek dem talk ‘bout it’….” he had said.

Beatmaker Ej Fya

During the interview, the Kittician gave some insight on the beatmaker for the song, which he had recorded approximately a year ago, explaining that he is an American and not Nigerian as he had originally thought.

“His name is Ej Fya and he is from California. I didn’t know that. I thought he was a Nigerian producer,” he explained.

Of his early beginnings in music, Messia explained that his go-to place for beats was initially YouTube.

“Dem time I wasn’t big to say I have my own producer, so we used to always scan through YouTube to find a beat an wi do wi ting. Purchase di beat an wi gone a road wid it. Suh wi have dis song almost a year now,” he said.

Messia also explained how the song, which debuted at No. 67 on the UK Singles Chart on Friday (June 2), took off. He said he traveled to Miami with Trinidadian artist Prince Swanny and went through the paces of promoting it where it was well-received, and that the song took on a life of its own when he did a live stream.

He also credited Spanish Town artist Govana as a close friend of his, who has given him maybe the soundest piece of musical advice: ensure his intro to the song is solid.

“The melodies that were used to create that masterpiece, like di intro alone just mek yuh waan bounce, want vibes. One ting Govana always teach mi ‘the first two lines of yuh song is going to be the entire song’,” he said.

Messia says he was only being honest about Jamaican music comments: “Mi neva grow up a listen Dancehall.”

In response to accusations from some Jamaicans about him “dissing Dancehall”, Messia also sought to explain that he was simply being honest when he recently described himself as a rapper and said that he was not influenced by Jamaican music.

In clarifying his point, he made it clear he could not be faulted for his choice, as he did not grow up listening to Dancehall, but was exposed to Kittician versions of Soca, as well as American Hip-Hop.

Messia also told Miller that he intended no harm when he made utterances about not being influenced by Jamaica, and that the Jamaican artists and producers, whom he associates with, unlike persons on social media, also have no ill feelings towards him.

“I have songs wid countless of producers from Jamaica. I have songs wid countless of artistes from Jamaica and I respect they craft and there is a reason why dem neva seh ‘oh you guh oneside’, all when mi seh weh mi seh. Right?” he added.

But as he made the comment about “seh weh mi seh” Miller immediately asked him to repeat, the comments to which Jamaicans had taken umbrage.

“Suh tell us what you said,” Miller told him in a nonchalant tone.

“Mi tell dem seh I consider myself as a rapper,” Messia replied.

“An yuh know wha happen to? People want mi to seh… dem want mi to cap. Dem want mi to lie. Dem want mi to come out here and be like ‘oh, mi grow up a listen Dancehall artiste’. Like no bro. Weh I’m from, mi neva grow up a listen Dancehall. At di end a di day a Dancehall music I’m currently doing. But, if I get di chance to do any other form of music, I am going to step up my game. I am going to show the world what I am capable of doing,” he declared.

Jamaicans had taken umbrage to responses Messia gave in an interview on The Fix Podcast that Jamaica did not have an influence in his music, despite him singing about topics unique to the island, including the Trap song MOCA in which he sings about the chopping lifestyle, and which makes references to Jamaica’s Major Anti-Crime Task Force.

“Nah man, a nuh influence dat. There’s no influence there,” Messia, who was born in Kingston and moved to St. Kitts at two months old, had responded in relation to MOCA.

Initially, in response to Miller pointing to his recent comments on social media which many Jamaicans touted to be a “diss” to the culture, Messia had expressed joy that he would now be able to clear the air.

“I was waiting for you to ask me this question out of all questions. First of all Sometimes people haffi just listen properly and comprehend before dem speak off the comment. How can I disrespect Jamaican culture disrespect when in Taliban, before di song buss, the biggest song; mi seh mi bawn Kingston? Inna MOCA, before mi even went an seh weh mi she, mi tell dem Yaad man a teach mi how fi do suppm,” he said.

Messia went on to dismiss claims that he was mimicking Jamaicans by using Patois lyrics, pointing out that the Kittician vernacular was similar to that of Jamaica’s and that even while he is able to speak like Jamaicans, Trinidadians and Kitticians, he chose to sing in Jamaican Patois.

“I don’t do Trinibad to be honest. I do Dancehall music…,” he said, adding that he was “happy to have different dialects” as he liked switching it up” but that his favourite was Jamaican.

“And that’s a next thing too that people don’t understand, di Jamaican accent is very similar to the Kittician accent. Suh a nuh like me a come an se oh mi a come try copy somebody an dem ting deh. And, I won’t lie, why I love di Jamaican accent suh much, it is more universal Caribbean language out of all Caribbean patois,” he said.