Dancehall, Crime And Leadership In Jamaica

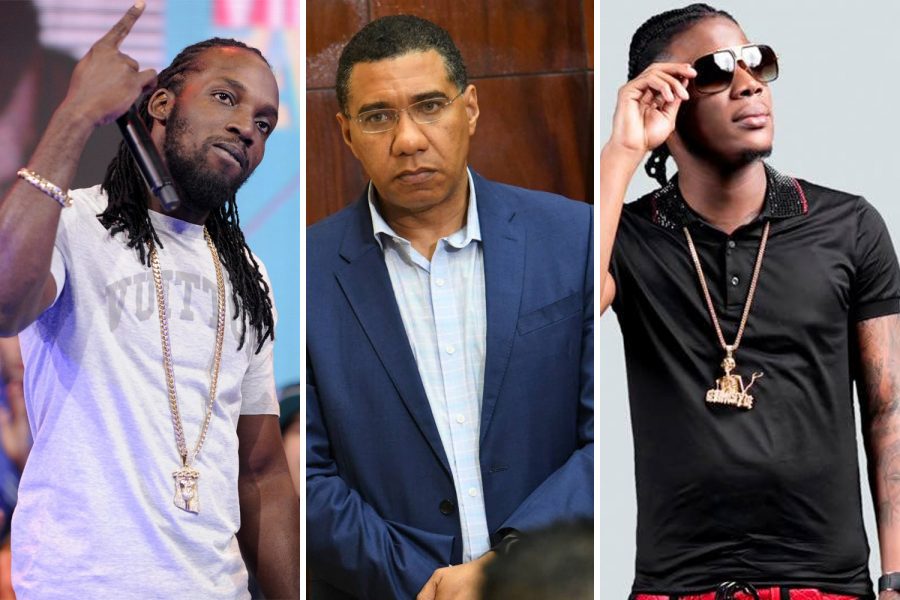

Dancehall artists have come out lashing, in a more sustained and visible way to respond to the most recent statement by Prime Minister Andrew Holness about dancehall lyrics and their link to high rates of crime and violence in Jamaica. Mavado, Masicka, Baby Cham, and Mr. Vegas among others have made public statements in recent days. My thought when I first saw reports about the Prime Minister’s statement made in Parliament was – ‘again!?’. Here’s some of what Hon. Andrew Holness said: “In our music and our culture, in as much as you are free to reflect what is happening in the society, you also have a duty to place it in context…” He went on to say “…Dat yuh tek up the AK-47 and tun it inna a man head … That is not right. And though you have the protection of the constitution to sing about it, you also have a duty to the children who are listening to you…” These statements have been interpreted as targeting dancehall, scapegoating, and a trifle hypocritical.

At face value, the statements are benign considering Jamaica’s longstanding crime problem. They come from a leader who is grappling with inordinate rates of crime and violence in a relatively small population. The statements acknowledge that artists have a role to play in shaping society and that their art can be socially responsible. It is well known that crime and violence in Jamaica which topped the murder rate in Latin America and the Caribbean in 2020 are out of hand. Since 1960, murder has been on the rise with spikes in 1980 reaching 889, again in 1997 reaching 1038, and 2009 with 1683 murders. While this figure dipped in 2014 to 1005 it was back up to 1323 murders in 2020 even with an ongoing pandemic based on statistics from the Jamaica Constabulary Force here.

However, there is more to it than that. While one can and must acknowledge that Dancehall artists are firstly artists who have creative licence, some of whom are not mindful of their influence and thus have not signed up to be role models or to take on the job of leading the youth of Jamaica, there is the other more grievous issue which explains the general tone of the reaction from ordinary citizens, not just the ‘articulate minority’. The statements were seen as hypocritical in their tone, and if you were observing all along, they were not new statements, and they have always been met with some amount of push back from the dancehall community. In particular, persons have commented on the hypocrisy around election campaigns that utilise dancehall’s creative products from the very artists who are never consulted on key social issues or incorporated into strategic planning processes for social engineering, including policing Jamaica, but who by virtue of their artistic works get either blamed or ‘prostituted’.

Like the classification of “Dutty Rastas” by citizens and successive administrations born out of disrespect manifesting at the highest level in various human rights violations including cutting of locks, beatings and displacement, the reggae and dancehall artists of Jamaica have suffered from negative perceptions, disrespect and exclusion. They are sometimes seen as the uneducated, lower class, ghetto poor who have nothing to contribute to the society except morally degrading lyrics. Let’s call a spade a spade. These are some of the reasons why scholars such as myself have found it important to document indigenous music and the larger culture supporting it. Even as perceptions have been changing there is still further to go.

So imagine the ‘clash artists’ swinging their ‘lyrical guns’ for a forward in the 2020 general election and then in the next breath blaming dancehall artists and their lyrics. That dub plate election saw some of the very same suspects who could be accused of recording violent lyrics and the seeming double standard to create hype around an election doesn’t need a magnifying glass for further clarity. Were they just all unaware that Spice, Dovey Magnum, the 6ixx Boss Squash, Shenseea, and Skillibeng have recordings which are not fit for airplay, some including violent lyrics? Were Members of Parliament including Hon. Andrew Holness simply willing to overlook this fact for a clash forward and not see the inherent double standard? An election is constitutionally due every 5 years in Jamaica. Many of the parliamentarians do not have any relationship with these artists and have no interest in their wellbeing, consulting them on matters around their status as artists, facilitating the success of the creative industry in which their operate or consulting them for community upliftment. There is a strained relationship between artists, ordinary citizens and the government as well as its apparatuses which are seen to foster antagonism, disrespect and suppression.

Here’s what I shared with the Jamaica Observer last year about the election clash:

“In the same way that we have been given these creative riches from our deejays associated with dancehall, I want to caution politicians who will forget after the election the very people who have provided these dubs for them. I want to caution them against doing that. We must be able to advance those creative riches we have been seeing on the campaign by the kind of investment that politicians are known to provide for health, fighting crime, building roads, enhancing constituencies, for even making sure people vote for them…We must be able to provide the creative industries in Jamaica with the resources needed so that those industries can be maintained. Just don’t be exploiters and culture vultures. Let us make sure that after we use those dubs and increase the popularity of those very artistes that the investment is made to sustain the industry. I say this with all seriousness, because we have been a Jamaica very much interested in using culture to advance our needs, but when it is time for real investment, to put our money where our mouths are, we fall short…”

The creative industries are crucial for advancing economies in the 21st Century. The global creative economy is worth US$trillions and while Jamaica’s name is called in every conversation about global music we are not earning value from our music proportionate to our global reputation. Most importantly where Jamaica is concerned, there is no way to speak about the creative economy and leave crime and violence out of the picture. Some may argue this is the case all over the world. While the case of Hip Hop has been raised with the glorification of gangster lifestyles, incarcerations and untimely deaths of its brightest stars, we don’t have to look too far for the association in Jamaica. There are dancehall stars who have been incarcerated, are currently incarcerated, have glorified masculinity tied to a life of badness and their influence while not seen as infectious is undoubtedly potent: the influence has to be acknowledged and considered based on Jamaica’s spiralling social problems.

All serious crimes from murder, shooting, rape and robbery to break-ins are on the rise. Since January 2021 we have seen media houses reporting on the murders which have already surpassed that for the corresponding period last year with 384 murders up to April 3, 2021. Therefore, 2021 is already shaping up to be a deadly year with deaths from a pandemic plus those from the civil war we are waging against ourselves. We are also seeing an increase in abductions, human trafficking and domestic abuse, in particular gender-based violence. Could this only be blamed on the music? No.

I take these matters seriously and I am sure the Prime Minister and his parliamentarians do too. However, there is a step further we must go beyond talk or blame. The seriousness of these social pathologies cannot be blamed on the music alone. Baby Cham puts into perspective the role of parenting, illiteracy, poverty, lack of opportunities for youth, and poor leadership as key contributors to the high crime rate, within his now-viral Instagram message here.

Violent content he pointed out is available in audiovisual streaming platforms such as Netflix and of course via cable channels. Most importantly, Cham raised the question about whether the PM’s comments were made from guilt or a study done. While there have been some investigations, no definitive study has yet been done to ascertain whether there is a correlation between crime in Jamaica and the popular music produced and consumed. Indeed, the artistry in music is a reflection of the social world and can be an influencing factor but it can also be a deterrent. While a lot of funds including from grants and loans are being spent to tackle crime, we might be witnessing a case of diminishing returns on those investments as we fulfil some of the obligations of funders versus a bottom-up approach being pushed by organisations such as the Peace Management Initiative.

Any Prime Minister who seeks to blame the music versus properly contextualising the complexity of crime in Jamaica which is mostly being tackled with a top-down approach versus systematic and sustained investment in changing the culture of policing and in particular, community policing, is going to be seen as mischievous and irresponsible. Such a Prime Minister must also be heard acknowledging the work needed around building confidence in police officers and the system which has been marred by accusations around extra-judicial killings, human rights violations, extortion and double standards in respect of abiding by the law.

Is it all negative? No. There is a lot of work to be done. Blaming artists and their music is going to be far less effective than engaging them in programmes to uplift Jamaica. Music remains a scapegoat because it is easy to imagine a link based on the lyrical content which reflects the pathological reaches of our civil war against each other. Why do we need to hear about whose marrow has to fly and who will be made into a ghost, some might ask? These are part and parcel of what has become reality in Jamaica, a part we can’t sweep under a carpet or dismiss with blame. For Jamaica, with the social problems I have described, reflecting life isn’t the only thing we need from the music however. There is a grave need to replace guns with musical instruments and the bad-mind tendencies with love.

Who is responsible? We all are. Every single one of us. But we have to stop blaming the music because it is nothing but lazy tongue lashing. Leadership to stem crime and violence requires bold, brilliant yet humble approaches to seek guidance from the very persons being blamed. We know that powerful voices such as Bounty Killer, Mr. Vegas, Agent Sasco, Tanya Stephens, Ce’Cile, Romain Virgo, Buju Banton, and others are using their platforms to vocalise and propose solutions. They are digging into their own pockets knowing fully well that the problems are shared, and solutions must also be shared. Why not engage them? Why wait for example until our youth are incarcerated to have rehabilitation programmes as the music experiment which saw artist Jah Cure produce the mega hit True Reflections documenting his lamentations about prison walls?

Statements such as those repeatedly spoken by the Prime Minister or other members of government over the years do not amount to any substantial move to stem the problems. There is need for a revamp of our educational system, especially at the primary and secondary levels. There is need for sustained public education around crime and the role of every citizen in stemming crime. We are now seeing what the challenges of public education look like with the COVID-19 pandemic and that it has to be systematic and sustained. It is the same with crime. Crime is Jamaica’s biggest problem because it is a symptom of deep-seated problems around power, respect, love and confidence. There is need for investment in educating every Jamaican. Smart choices away from crime and violence can be conditioned through viable education and job creation.

Most importantly, the way to clear the air on the link between violence and the music in Jamaica is to commission a proper study. I have developed an instrument to be administered and there are competent researchers here in Jamaica to execute such a study. The solutions are not difficult, and they most certainly do not involve a top-down approach or statements that seek to blame the very artists who have worked very hard to put Jamaican music on the world map. Once and for all, can we get a workable crime plan centred on building our communities, valuing the human rights of Jamaica’s citizens and with our creatives playing their rightful role instead of being blamed? The political will is what we need to build communities.