Interview: Tanya Stephens’ ‘Gangsta Blues’ At 20

By 25 years old, singer Tanya Stephens had already scored several Dancehall classics, and was in a league of her own as a songwriting virtuoso. But she was also facing an existential crisis.

“I was coming from hardcore dancehall which was primarily my identity,” Stephens told DancehallMag. “I wasn’t really given the room to explore anything else, so every producer would say, ‘I want a song like Yuh Nuh Ready Fi Dis Yet … I want a song like Handle the Ride ’. I’m like, I’ve made those songs already. Don’t you wanna hear the new songs that I have? And they just kept pigeonholing me and I was very frustrated.”

So she ran away, literally. The St. Mary native relocated more than 5,000 miles to work in Sweden with Warner Music. The partnership empowered and expanded her creations, evidenced by the soft-pop Sintoxicated album released in 2001.

“It wasn’t really what I set out to make, but it was an education because I learnt that I could do different,” she said. “It was confirmed that I was so much more than just body parts and sexual activity. I could make more meaningful but deeper stuff, and dip into life because we’re not just sexual creatures; we’re social creatures… It was really a big relief to be able to explore the other parts of me.”

But the relationship with the label didn’t pan out as expected, leaving a heartbroken Stephens returning to Jamaica with no desire to record music. Eventually, her tribe convinced her otherwise, and the result was the critically acclaimed Gangsta Blues , which turns 20 on Saturday.

Follow DancehallMag this week for details surrounding the accompanying anniversary tour, stories behind songs like It’s A Pity, and Stephens’ experience working with local versus foreign acts. But first, the musician takes us back to creating the sexual and socio-political 17-track masterpiece, songs from which she’ll be performing tonight at District 5 in Kingston.

In reflecting on Gangsta Blues , it’s remarkable that by 30, you’d had all these experiences across love, relationships and hardships, to pen a body of work that activates and exercises the mind – thrilling with literary elements. That’s how you start the album; this spoken word-of-an-intro which communicated that you’d endured and learnt a lot, and was about to shame anyone who’d ever doubted or compared you. Can you give me some context into what was happening in your life/career that caused you to start the album that way?

I wanted to do more. I feel like we’ve done an injustice, a disservice to our genres, reggae and dancehall. We’ve put our people in a box and claim that ‘dem nah go like that, it’s too pretty…it’s too deep’. What we’ve said with the music is that we’re a rough, uncouth and unintelligent society, like Jamaican people or the diaspora can only understand very shallow, very trife things, and I proved them wrong. So, it wasn’t only just for me. It was for all of us because our people ran into my new direction… They welcomed me with open arms and was like ‘you’re a breath of fresh air’. Everybody said that, from garrison to gentry.

You came out of the 90s with notable dancehall hits, went soft-pop with Sintoxicated, then Gangsta Blues comes a few years later which has reggae, dancehall, spoken word and blues. What’s the meaning of the title?

The title kinda summed up where I was in my head. When it comes to telling stories, I’m a blues kinda person. I tell human stories in my music and because it’s usually stories of tragedy and heartbreak, it’s kinda more along the lines of blues. But my genre isn’t blues, my genre was dancehall and reggae fusion. Mi also nuh really soft and whiny. I am more of a gangster, mi fight back, so mi tell my blues wid war inna it… My blues is ‘gangsta’ and that’s where I was in my head when I did that set of songs.

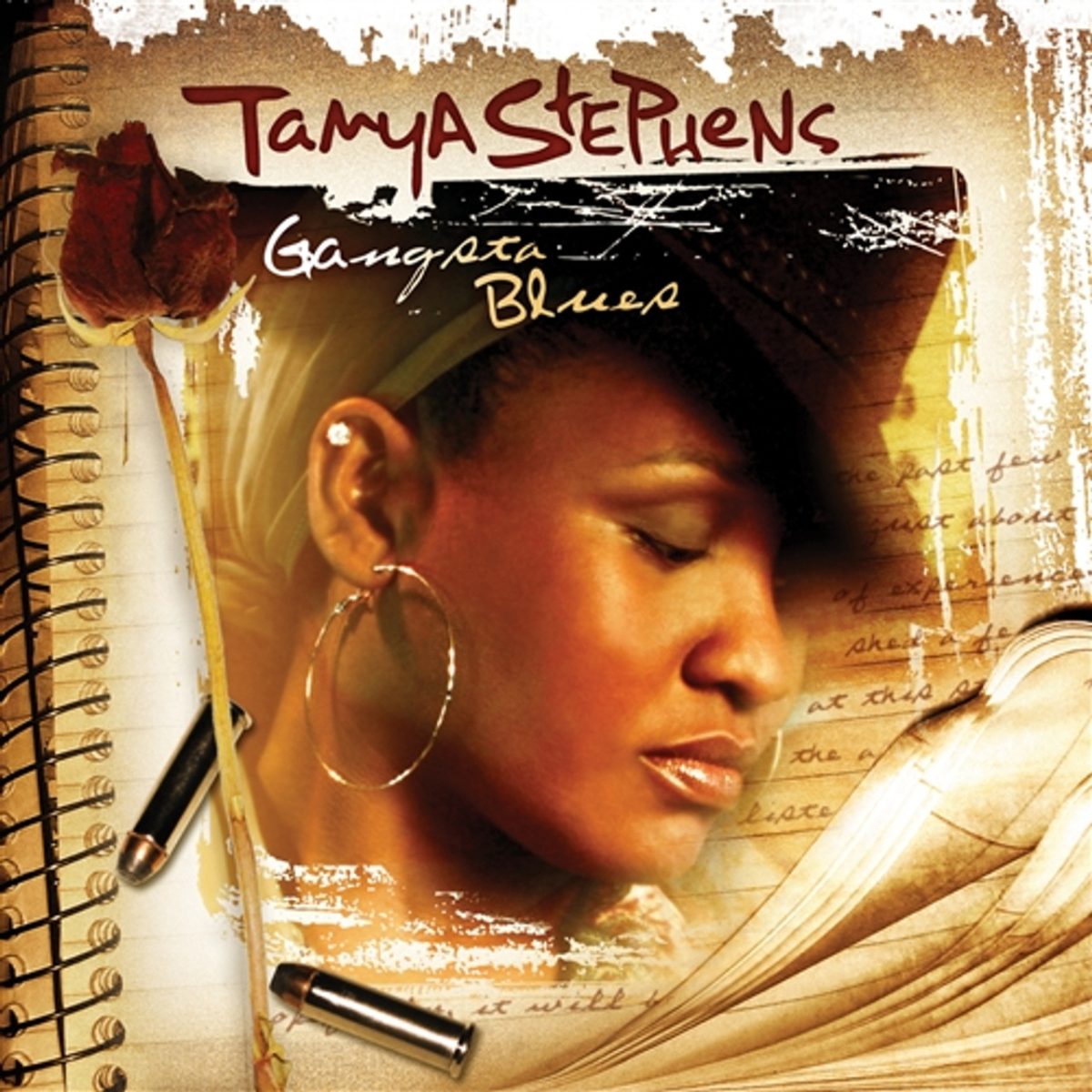

Looking at the album artwork, there’s this dairy with these scattered bullet casings. Your makeup was neutral, you’re rocking some hoops. What’s the symbolism of the cover?

I had a conversation with the art director at the time (Kerry DeBruce) and she turned out to be the best person for it cause she understood completely what I was saying. You see what I just described to you? We had a conversation about what was in my head, what was going on, and she was like, ‘cool’, cause I was writing – I write down everything. My music is like a diary, so she decided she was going to give me all the elements from where my head was at the time.

When did you actually record it?

Writing isn’t time-specific, so there are elements which were written before I actually started putting together that body of work. So, the creation process was longer, but the recording of it, I would say, was about a year and odd.

Was the project intentional or did it come together over a series of recordings?

The collection of songs was very intentional. I like music that flows very cohesively. I like a thread; I don’t like mismatch. I don’t like when people just go out and grab together a bunch of songs weh nav nothing fi do with each other, and call it an album. Mi feel like that’s disrespectful to my ears and my pocket, so mi never waan do that.

I noticed that the majority of the songs were produced by and co-written with Andrew Henton. How did you two connect to decide to work on this together?

We were introduced by his father who was my producer at one point, and he was appointed as my road manager. As my road manager, we spent a whole lot of time together on the road… He’d been aspiring to make music, made beats and was rapping and doing other stuff, and so we started listening to each other’s stuff and realised we have some compatibility where that is concerned.

We started working because he had no preconceived notion as to what my music should be.. He was perfect for me because you know when you work with these old producers in Jamaica, they want to tell you how to do things. He didn’t have that… That’s how we ended up working together; just two people weh waan do something but we nuh really know what we doing, 100 percent, which is good cause then it means you have an open mind.

The album was released by VP Records and Tarantula Records, the latter of which you founded together?

Yes. A lot of people don’t know I was the one recording most of my vocals myself. I was my own engineer. I didn’t mix, but I prefer to record myself because I know when I could push me more, and I know when it didn’t make sense to push me more. Nobody could know me as well as I do, so I got things out of me that nobody else could. I was willing to experiment where other people would have said, ‘No, that don’t sound good. Go do it over, do it this way’. I never said that to me once. Anything that crossed my mind, I tried it, and if it didn’t turn out right, then I just discarded it cause it nuh cost nothing fi try.

Okay. I heard you say that you recorded yourself for Some Kinda Madness (2022), so you’ve been doing this?

Yes. I was introduced to that concept when I went to Warner. They actually set up a studio in my home when I was living in Sweden and put me to work, writing by myself, and that’s when I started. By the time I came back to Jamaica, I already had that concept in my head, that I could take my own vocals. I brought back my equipment with me and started working.

Cool. The album starts with Way Back which centers the listener on appreciating the art of music, minus the fluff. You sing, ‘Take me to another place, another time, better hooks, better rhymes, stronger lyrics, every line’. This has been a conversation today as it relates to lyrical quality and creativity. If you felt that way two decades ago, how do you feel about the music landscape now?

Surprisingly, way more positive because I will be the first to tell you that that was a very myopic view I had, and I feel relief that I am willing to grow from it because it was my personal opinion. Right now, if I had an opinion like that, I wouldn’t share it because it’s my personal opinion and I really shouldn’t put that out in the universe to become solid. I should try to find what it is that these kids need and see if I can provide it… We’ve kinda ostracised them but we shouldn’t because our parents did that to us too. They used to say, ‘The good old days’, but if all the old days are the good old days, doesn’t it mean that these days, right now, must be good, they’re just not old yet? We shouldn’t make only old things be good, but I don’t regret having that perspective because all my perspectives sum up to me.

And as you often say, your philosophy can change with new information.

It did, and I’m very happy it did. I want to tell us that everything is fine and there’s nothing to worry about. Music is safe – it’s always been safe. Music can never die. Music is the expression of us; it’s our vibration, it’s one of our frequencies, so we’re fine.

Moving on to Boom Wuk, and can I say, every time I listen to those first few lines, I have to laugh because I feel like you’re dissing the guy. It’s not your beat up car, you definitely ain’t no movie star… Yaa compliment the boss or not?

Isn’t that what they do to us all the time though? The likkle back-handed compliments. You’re cute for a fat girl. You’re pretty for a black girl? Don’t they do that to us everyday? Alright then, come through.

Valid. Boom Wuk is rich with visual imagery which is a songwriting strength of yours. Your sister was a literature teacher which connects the dots as to why you’re such a dope storyteller. Even on Damn, you give us spoken word and make us feel like a fly on the wall on this almost-perfect date night. We can see this restaurant, we can see him walking you to the car. How did your affinity for literature resurface when you were writing for Gangsta Blues?

My writing, my creativity, the literature, it didn’t resurface – it never left. It’s in everything. It inna mi dark humour. Mi have a very twisted sense of humour. Some of my friends have called me macabre and I love it. It’s never left and that is why I kinda had this, weh mi call my first existential crisis, because dancehall wasn’t allowing me to express that. It was limiting me, telling me what I could laugh about, write about, what topics were safe, and I didn’t think any creative should have those limits. When I left, I got to explore all of it and it sounded like something new, but it was not new. It’s who I always was and who I always intend to be.

Your gift to weave a captivating story continues on Little White Lie, and I have to confess, I just discovered Ricky Lake in February and it hit me like, that’s what Tanya had referenced on Little White Lie. The song impresses in many ways. Again, we feel immersed in this woman’s predicament. We see this child tauntingly singing ‘daddy, daddy, mommy made a boo-boo’. You were able to address what we call “jacket” in Jamaica in a sentimental, reflective and expansive way. What’s the story of this song and your approach to the topic?

The story is, as you said, age-old; it’s a Jamaican staple… I grew up with several jackets and it felt like the story was not explored in its entirety from – to me – the most important angle. Just thinking about who fertilise an egg, it’s not a big deal who raise a pickney. Kids need parents and I think many of our men took ribbing and shortchange themselves because them miss out pon a great kid weh really and truly, a dem dem know as a great father. The pickney nuh care who fertilise dem. Di pickney just know the man who dem open dem eye and see deh deh fi dem from day one, and I felt like the story needed a more human touch than ‘lawd, she give the man jacket’. You need to see the thought process because it’s the same as with abortion, which I’ve been trying to figure out how to take on and humanise it because most of the people who do these things, they suffer for years in silence… They have to take that secret to them grave. It’s not a bragging rights thing. There’s no glory to be had from giving a man a jacket, nobody praises you for that.

If it’s a man weh you love, you suffer even more because you’re hurting the child, yourself, this man that you love. You don’t need a hell for that; you’re already living in your own personal hell that you create in your mind every day with the guilt that you carry, so I just wanted to show the story from another angle. We always need to stop and look from another angle.

Then comes the Doctor’s Darling hit and for many, the star of the album, It’s A Pity. You said you wrote it while enroute to the producer’s studio in Germany. We’ll carry a special story on the making of that song, but did you have any inkling of it taking off and becoming the classic it is today?

I never have anything like that. When I’m writing and recording, I don’t think of commercial success. I feel like that is a deterrent to making a good song because then you start to look around to see what people like. If you look around to see what people like, you will only make the thing that has already been made, you will not make a new thing. So, I never think about that. I make what I genuinely feel inside of me.

You have side-chick buyer’s remorse in Tek Him Back, but switch roles to the devout wife in What’s Your Story? and even Can’t Breathe. How deliberate was it in balancing the perspectives of the wife versus mate?

That was a happy coincidence because I wasn’t setting out to put them in the same body of work… I like to look at everything from every perspective that is available to me. I’ve seen women like this in the After You. I’ve seen women like the Can’t Breathe. I’m more like the Tek Him Back kind of person, but I do have elements of every other kind of personality type in my life, and I love and care about them very much, just as much as I care about myself in my Tek Him Back state. I have seen women who men left and sum them up in only financial terms. ‘Well, you didn’t work so you didn’t contribute to the economy’, and that’s something that still bothers me because we don’t quantify effort in any honest way. Fi tear out your belly for nine months, multiple times, when all dah man yah have to do is come in, have a good time, ejaculate and gone. You are left bearing the fruit of that seed for nine months, and the first trimester is a hazard. This is something that threatens the woman’s life; this is a parasite living inside of you. If you describe it biologically, that’s what pregnancy is… When you do that for a man five times, and him tell you say you nuh fi work because it better for you, him make enough money for the two ah unno, and then him suddenly tell you say the money a nuh yours. But like, I would have been working, so you have to calculate how much money me neva did a mek.

Just like when you have an accident, somebody crash into your car, them make your car can’t work, you broke your foot, your neck inna brace, and you can’t go to work… When you sue them, you calculate, in a civil suit, how much money you lose. How we nuh know how to apply that to pregnancy? You have to calculate how much money me lose by looking at my qualifications, potential, what my plans were before you intercepted me and tell me ‘don’t work’, and then multiply that by time, pregnancy and everything else. Then you would realise me worth more than weh you have, but I am willing to settle for half of it. And so, even if I’m not in that position, I’m still able to understand and appreciate the position, to empathise… If you empathise, you can figure out any situation, any position.

To hop on Can’t Breathe for a bit, it articulated the sometimes suppressed thoughts of the woman scorned, and how dark and extreme that can get. The entire lyrical makeup of the song is something, to this day, I’ve never heard in reggae (After You being and the closest rival). There’s a point in the song where you said he’s moved on and you hope his woman leaves him for a girl. Did you get any backlash for expressing such a thought in 2004 when the local music scene wasn’t as accepting or tolerant of the queer community?

Mi enjoy one very peculiar position inna Jamaica music scene where mi nuh really see many people get dah license yah, and mi give thanks for it, but I think it’s because mi honest with them… Mi nuh think a everybody coulda seh these things or it might have to do with the way I say them too. I never got backlash for any of these things. What I got was surprise, discovery, people come and seh, ‘My girl, mi nah lie, mi never think about it that way before’… That’s all I wanted. With the scorned woman and being able to express that, look here, all of we have these thoughts. We gwaan brand new and we pretend, but I don’t lie about my depression. I don’t lie about my anger or these things because all my parts are valid, and I am going to express every single one of my thoughts because me have respect for my complete being, and mi nah go diminish me fi mek room fi nobody else imaginary parts…

I don’t feel like it makes me look any less of a person or worse if a man lef’ me and me feel hurt. Granted, mi never really have dah position deh because mi kinda grow up with the idea seh if somebody lef’ weh mi did a start get attached to and mi feel one way, mi just find somebody replace dem real quick. Mi know seh it toxic as hell but when it comes to pain and hurt and healing, mi work with the moment. Mi do whatever it takes in this moment fi get from this moment…

You have your own rendition of Helen Reddy’s I Am A Woman which complements the album’s intro. It’s interesting to digest now as I was watching you on NandoLeaks recently where you said you regard yourself as a man in your industry. How do you reflect on this cover in the backdrop of that statement?

I am definitely a woman biologically. I’m a woman and all of my social experiences are from the perspective of a woman, but when I walk into commercial spaces, I realise being a woman gets me no points. It doesn’t even get me equal respect and I want and demand equal respect, so I become what they respect in their space. It’s not like I’m going to grow a penis… But when I stand in their space, I make it impossible for them to see me as a girl because if a badness dem a do, mi a do badda badness. If I were in a lyrical space and when the men stand next to me, when I’m not in the room, they can say anything they want, but when I stand next to them, they know they’re not my superiors. We can probably debate whether they’re my equals, and I will allow you to say they’re my equals. I don’t think they are. I’ve never seen any evidence of them being my equals, but one thing we can be sure of is they’re not my superiors, so no man cya see me as anything other than the best and they see me as the best, so dem haffi see me as a man.

The tone and theme of Gangsta Blues shift as it is drawing to an end. You have these socio-political, blues songs. Sound of My Tears, which at parts, literally sounds like you’re weeping; The Other Cheek and What a day, anthems for the marginalised which highlight that you’re no newcomer to advocating for the betterment of people, and holding leaders accountable. We’re going to delve into these songs in another story. You culminate Gangsta Blues with We A Lead, echoing the self-validating message that starts the album. Why did you end on this note?

I felt like it needed to be said… It felt like I didn’t know any other artist in Jamaica or elsewhere that got as much persecution as I did. Other people could have done something and just pass, and when I did it, I got judged differently. One radio personality even told me that when he would be willing to accept certain things from other artists, he wouldn’t accept it from me because ‘I knew better’. But I’m like, it means that the act is not significant. You’re not judging the act, you’re actually judging capability, and who does that? It means the standard is flexible, therefore there’s no standard at all… I got stuff like that from so many people and I don’t think they realised they were doing it, but it actually made me better and it kinda made me a little bit more egotistical because no matter where they put the bar, I surpassed it by jumps. So, it was the best thing for my product; it made me push harder and do more.

It wasn’t the best thing for my growth process because it made me really egotistical because when they didn’t play me, I realised I could do without them. When they criticised my work and acted like it wasn’t the best and I still went and surpassed what they criticised and everybody else said I was the best, it wasn’t good for me. Fortunately, my process really was about growing, so I caught myself and checked that and insulate myself with people who hold me accountable…who weren’t into the ‘Tanya Stephens’ thing, and the biggest of that being my daughter who never fraid fi be like, lady you a mek nuff noise, stop the noise please… Mi lucky mi escape that but mi did haffi come out braggadocious. You know how much things dem seh and do bout me inna dancehall and it’s so dumb because the music space is a workplace, it’s an industry, and it’s not just one artist strive off it. So, the bigger the industry becomes, the more success contained within it, is the better it is for everybody, even the man weh a sell cane outside of the dance…

We’ve never been able to understand that, so that’s why we have the ‘crab in a barrel’ mentality where we fight each other instead of being happy for each other’s success, and wanting each other to grow. Each artist pretend seh they can service seven-odd billion people on the planet. It is the dumbest thing ever and I had to say it. I was competing with people weh me and dem nuh inna the same class, in no way, and I couldn’t understand that and it was fed by people who should have known better, who should have made the distinctions and it wasn’t even about better or worse as far as me and other artists, as it’s about different. They should have celebrated our differences instead of pitting us against each other. They exploited that, trying to generate some kind of activity from animosity. They fed on insecurities when they were supposed to just reassure somebody and seh, ‘Dem nah tek your place, dem create dem own place’. It just kept growing and growing and I had to come out and be like, listen to me and listen to me well. We are not the same. We might both be crawling, but I am a caterpillar and you are a worm. I am going to become a butterfly, you’re going to stay in the dark.

Is there anything you want to add that wasn’t asked?

Me just waan seh thanks to everybody who made Gangsta Blues the classic that it is because making it is one thing, but it could have been the best album made that nobody listened to. Big up everybody who played and bought it, made gifts of it, introduced new people to it and continue to, and people who are now streaming it. Big up the people who bootlegged it too because they spread it just as much and I really appreciate them. Thank them for coming to meet me on the road and coming to the concerts and singing along and helping me to perform these songs. Thanks for the online engagement when mi get into virtual spaces. I don’t have any complaints where my career is concerned and where Gangsta Blues, especially, is concerned. There has not been anything from the audience that has been less than just amazing and I really look forward to celebrating the 20th anniversary of Rebelution with them in two years time. I’m a very lucky artist with nothing but thanks to give.