The Rise Of Obeah In Dancehall Music

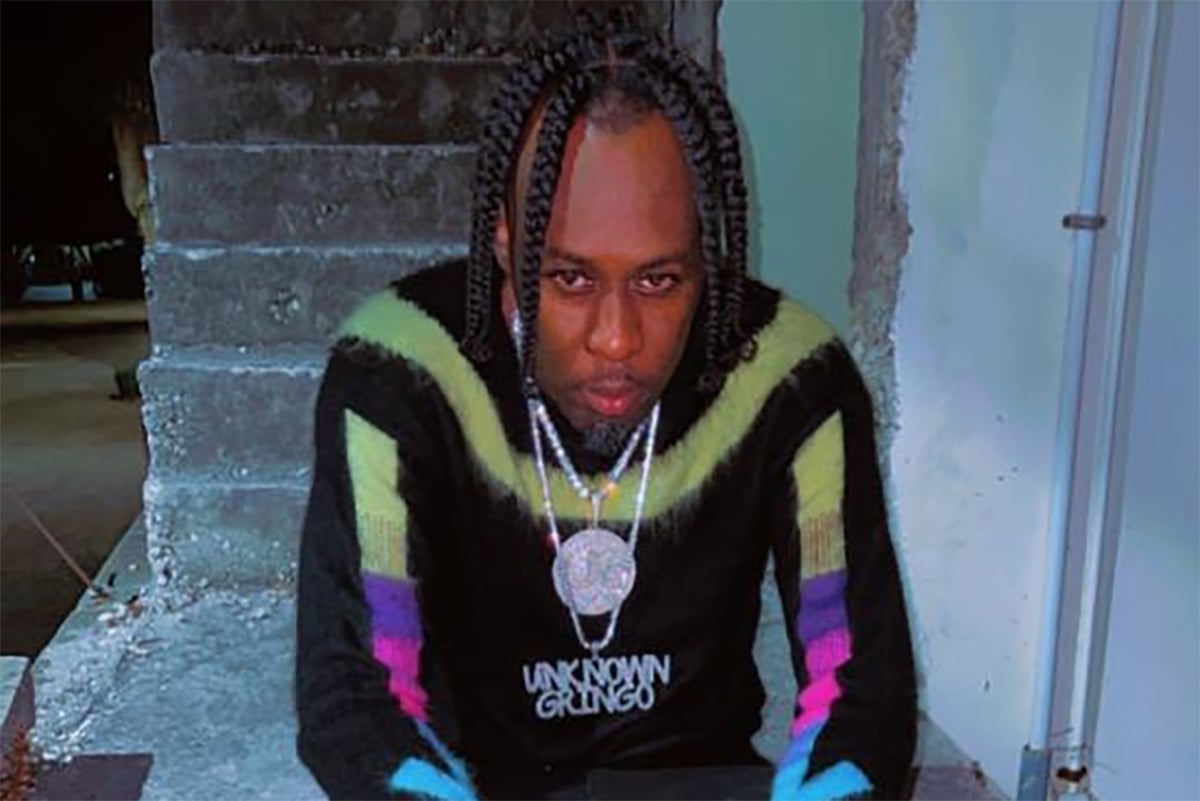

Dancehall artist Unknown Gringo is well aware that there is a connection between lotto scamming and the use of obeah to protect the ill-gotten gains. He is not surprised that the broadcasting of obeah practices has become a fixture in local Dancehall music over the past two years.

“Obeah has been a part of Jamaican society for a long time, science has always been around. Lovindeer sang about it way back and the young youths dem a use it as a storyline because music is art, a creative force, and dem a sing trap music and some ah dem a hustle in the game so dem a sing about dem lifestyle,” Unknown Gringo reasoned.

He said that the Dancehall artists sing about a variety of obeah paraphernalia in their songs.

“Dem sing about the ‘Fast Luck’ candle that when you light it, it help yu make money, dem sing about guard rings, money-drawing candles, clearance soap, and the more it work, the more dem do it because dem a mek money,” he said.

Apart from protecting the protagonists, scammers claim that ‘science’ helps them to “tie” their victims, so they can squeeze every red cent out of their finances.

“Whenever you pass a candle shop, yu will see all four Mark X park up,” Unknown Gringo said, laughing.

He said personally he used to sing about splashing on ‘4-7-11 cologne’ on his skin, but knows that life comes with ups and downs, whatever one decides to use.

“Power lies in words, belief kills and belief cures, if it works out for them, dem nah go stop do it,” he said.

According to Unknown Gringo, today’s generation of artists seems to find the topic of obeah less verboten than their peers before them. One only has to listen to recent dancehall hits to see the corollary between obeah and scamming. Valiant’s St. Mary includes references like “we ah work the Guzu hard and ah chap up the line”, and “every money haffi pay because mi rub down with oil”, while RadijahWild’s asserts on Another Day, Another Dollar: “send a duppy fi give yu cancer’.

The late Insideeus scored a hit with the ode to the guard ring called ‘Guard Up’ before he was gunned down brutally years later.

Unknown Gringo himself even released a new song recently called Sacrifice where he deejays: “get the ram goat, parchment paper, light up the candle, mek the skull sell the acre and send mi the paper”.

“Animal sacrifices are done in the bible and it still a gwaan with the Jews and Arabs dem, dem kill goat and sheep, people in Jamaica kill fowl to sprinkle inna dem building foundations, ah just part of society, part of the world, is almost like tradition,” he said.

Unknown Gringo is not surprised that today’s youths have no compunctions about revealing the sources of their success, regularly making references to ‘baths’ and ‘body washes’, guard rings, spray, candles, incense, oils, and handkerchiefs…yes handkerchiefs.

“Is just business, American rappers wear rings with the goat horns on them, is a commercial ting, mi see candle shop inna the UK, science de all over and it couldn’t happen if the corporate world never agreed with it. Look at how American rappers sing violent songs, and get millions fi sign fi sing about violence to send people to prison so the major corporations can benefit, ah so the world run. You’d be surprised how many upper class people wear guard rings and buy the same candles the youths dem a sing bout,” he said.

The wearing of guard rings in particular is a very common practice that runs like a fault line through the Jamaican society and includes judges, upper-crust businessmen, ‘Lodge members’, police officers, dancehall and reggae entertainers, inmates, criminals, politicians, teachers, and even teenage students.

Last year, a 16-year-old was stabbed and killed in a dispute with another student over a stolen guard ring. So it is not just scammers who have been relying on the occult for their safety, survival, and protection.

Some ethno-cultural experts theorize that obeah is part of the island’s African retention, given that most Jamaicans can trace their ancestral lineage to the continent of Africa. Obeah is set to remain a thriving business in Afro-Caribbean societies even though the practice was outlawed with the Obeah Act.

“Yu caan legislate against obeah, that’s why the police nah lock up nobody again for it. How yu can trace obeah? Yu ah go need a special detector. It no mek sense abolish it, just leave it because nobody caan enforce that in these modern times. Obeah legal already, nobody caan stop it,” he reasoned.

Obeah was first made illegal in 1760, when the British colonialists were spooked by the blood-curdling violence triggered by Tacky’s Rebellion.

This war was one of the most significant slave rebellions in the Caribbean during the 18th century before the Haitian Revolution, which began three decades later. During the 18 month uprising, 60 whites were killed, and over 500 Black men and women were killed in battle, committed suicide or executed after British military suppressed the revolt.

At the time, the rebellion’s leaders were advised by obeah men who offered spiritual protection as they resisted the oppressive reign of the British colonial masters.

At one time, Jamaicans were regularly prosecuted for practicing obeah, but for decades, the local police have not enforced the Obeah Act. Still, the championing of the practice has caused some people to call for the repeal of the act. Rubbish, Unknown Gringo says.

“Is modern times now, yu caan stop obeah, yu have white magic, three card man, psychic business, ah old time business that. When last yu hear dem lock up somebody fi practice obeah?” he asked.

Diana Paton, a professor at the University of Edinburgh, believes that obeah is a part of Jamaica’s cultural and historical history, especially those of the lower classes.

“The primary function of Jamaica’s Obeah Act has been to reinforce class and race hierarchies,” she told DancehallMag.

Panton echoes Unknown Gringo’s sentiments as she doesn’t believe a repeal makes much sense either.

“Repeal would make little difference to everyday life, because the act is never used. But it would indicate that the country no longer endorses a law initiated to protect slavery and renewed to symbolise Jamaica’s hostility to its African connections. It would be a rejection of cultural colonialism,” she mused.

Paton is the author of The Cultural Politics of Obeah (2015).

According to Paton, until the 1950s, Jamaicans were regularly prosecuted under the Obeah Act for all kinds of religious rituals.

“In the early 20th century, balm healers, Revivalists, Garveyites, and people who later joined with Leonard Howell to form Rastafari were all prosecuted for obeah, even though many of them were resolutely hostile to obeah themselves,” she said.

Paton said that many laws against obeah have been quietly repealed or revised away in other territories in the British Caribbean. Obeah was decriminalised in Anguilla in 1980, Barbados in 1998, Trinidad and Tobago in 2000, and St Lucia in 2004. In Guyana, the government last year announced its intention to remove the crime of obeah from the criminal code.

“In Jamaica, the last conviction for obeah that I found was that of Cindy Brooks, in 1964,” she said.

She said that in other Caribbean territories, obeah laws have been repealed.

“Over the last generation, many laws against obeah have been quietly repealed or revised away. Obeah was decriminalised in Anguilla in 1980, Barbados in 1998, Trinidad and Tobago in 2000, and St Lucia in 2004. In Guyana, the government last year announced its intention to remove the crime of obeah from the criminal code. In Jamaica, the last conviction for obeah that I found was that of Cindy Brooks, in 1964. The last arrest for obeah I located was in 1977,” she said.

Paton noted that ‘until the 1950s, Jamaicans were regularly prosecuted under the Obeah Act for all kinds of religious rituals’. In the early 20th century, balm healers, Revivalists, Garveyites, and people who later joined with Leonard Howell to form Rastafari were all prosecuted for obeah even though they did not believe in obeah practices.

Paton said she is not familiar with the current crush of dancehall songs glorifying scamming and linking it with obeah.

“The mingling of white collar crime and scamming with obeah causes concerns,” she said.