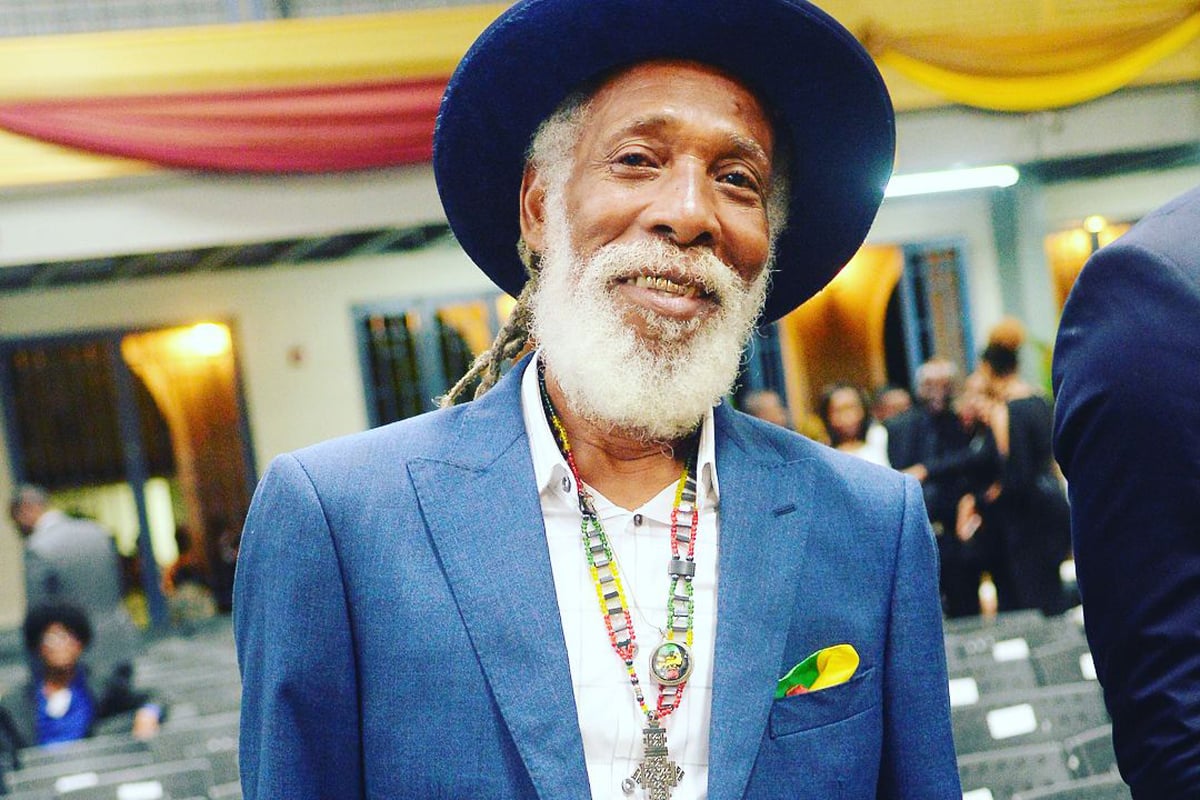

Big Youth Says He Influenced Musicians Of His Era To Turn To Rastafari

Pioneering deejay Big Youth, says his acceptance of the Rastafari faith and sporting of dreadlocks in the early 1970s, was what inspired the Reggae musicians of his era, such as The Wailers and Dancehall legend U-Roy to start locking their hair and penning Rasta lyrics.

His revelation came during an interview with Television Jamaica’s Anthony Miller on The Entertainment Report which was aired on Friday night.

According to the Dreadlocks Dread artist, the transitions made by the artists began some time after he recorded his S-90 Skank hit in 1972.

“Wi took a bike into the studio and create a lyrics…and I seh: ‘right now riddim hol I, riddim wild’. That music was so powerful, cause dat is where me start chant ‘Jah Jah wa wa wa’. Is dat bring di whole Rasta ting to di music, cause Daddy U-Roy was: ‘pow chick a bow, chick a bow’. No feelings against Daddy, caw I rate di man, but is a spiritual message that I was telling people fi ‘check fi Jah’. ‘Nuh badda simma dung an bend dung low’,” Big Youth said.

“U-Roy neva used to wear dreadlocks. But Big Youth come and teck it up powerful that U-Roy haffi dread. Bob Marley and The Wailers were in the Soul Revolution and when dem watch dis likkle man a ‘Ja Jah wa-wa’, and flash him natty and everything – and meck a tell yuh, in a year or couple months afta dat, everybaddy start seh ‘Ras’, bredrin,” he said.

Big Youth, who is known for hits such as Screaming Target, Chanting Dread Inna Fine Style and Hit the Road Jack, explained that during those days the music was centered on doing cover version of American songs, and the lyrical content of the original songs of the time, did not have the Rastafarian spiritual influences. Rastafari, he said, came in the music “when big youth come in”.

“Cause wi have di mystic revelation of Rastafari and all those people, which is the same genre but, a different one. The music was in a state where a lot of people didn’t even believe Rasta could have make it.

“Yes, I. Most of the songs that we were gyrating to are foreign music enu. Caw with all these – Paragons, John Holt and all these people, Heptones, they were only singing over. Now and again they make a (original) song,” Big Youth explained.

“So when we teck a version of one of these songs we are telling you what is happening and what you should do. Das why dem seh Reggae is the heartbeat of the people, because it is a message,” the 72 year old said.

Big Youth’s musings are similar to that of Jamaica Music Museum’s Herbie Miller, who, in a Gleaner article a few years ago, noted that in the early days of Jamaican popular music, the country produced many outstanding harmony groups, such as Higgs and Wilson and Alton and Eddie, groups such as the Down Beats, The Paragons, The Heptones, The Gaylads and The Wailers.

“All were outstanding groups that copied the styles of their favourite American counterparts, even covering their hits,” Miller wrote in his commentary.

“Some as much as adopted the names of foreign groups or applied to it some slight adjustment. Many dressed in fashions similar to the ‘brothers’ up north and even twanged when they addressed audiences. Though outstanding and well received in the role of clone, many lacked originality – the ability to display any real authenticity or inventiveness,” he added.

Said Miller: “Indeed, the local recording industry began in earnest in order to fill the void caused by the unavailability of the type of doo-wop and rhythm and blues songs that were popular in Jamaica but on the wane in America.”

Big Youth who was born in Downtown Kingston, said people revered deejays like himself back in the day, regardless whether they were from communities which were at “war” with each other.

“Live it up. I could walk di street bredrin. If I touch di street from here to Jungle and anyweh, peole just follow m jus like dat,” he said.

He said however, that before he exploded on the music scene with S-90 Skank, his community was impacted by violence, and music, therefore, was his way out of the quagmire of political violence affecting Kingston’s inner city.

“My life was ignorancy because if yuh live ova Tivoli, yuh caan come ova Matches Lane unless oonu a fire shot pon one anodda. Within the environment you have allies – gangsterism, is not some something that is new,” he said.

“I feel God give me a vision – out a di depths I cry – an know seh running up and down and fighting one anedda, that is stupid,” he said.